|

|

THE OLYMPIC FESTIVAL IN ANTIQUITY

Greatest among the

known religious events in Greek

antiquity was the Olympic Festival,

dedicated to the god Zeus, supreme

head of the ancient Greek Pantheon.

The Olympic Games have their origin

at the site of an important cult

sanctuary at Olympia in the

territory of Elis, 10km inland in

the northwestern Peloponnese. Near

the convergence of two rivers, the

Alpheios and Kladeos, on a low,

pine-covered hill bearing the name

Kronos, the father of Zeus, is an

ancient shrine called Altis, or

‘grove’ in the Elian dialect. A

number of altars located in this

area suggest that at least 6 other

deities enjoyed cult worship here.

From the 10C BC, Olympia imposed its

authority throughout the Greek

world, gradually developing from a

humble cult site to an elaborate

sanctuary complete with temples,

secular buildings, statuary, and

athletic facilities. By 776 BC, the

Olympic Games were being held on a

regular basis for five days, once

every four years, during the hottest

days of summer. Following many

sacrificial offerings, the most

magnificent of which was the

offering of 100 head of cattle at

the altar of Zeus, began a series of

athletic contests in the stadium,

the hippodrome, and other designated

areas at the site. Thousands of

spectators came from all over the

Greek world to witness the games.

Hostilities were suspended for the

duration, which meant that all Greek

city-states could participate. For

however brief the time, under the

sacred mandate of the Games, the

Panhellenic world showcased the

ideals of cooperation and political

unity. The Olympic festival,

therefore, is the paramount symbol

of the spirit and unity of Ancient

Greece.

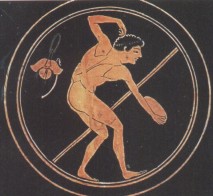

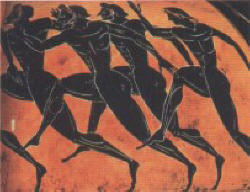

The athletic

contests, or agonas, held at Olympia

included foot racing, wrestling,

boxing, the pankration, equestrian

events, and the pentathlon (running,

jumping, javelin, discus, and

wrestling). All Greeks, with the

exception of women and slaves, were

allowed to compete. Victory at the

games brought glory not only to the

athletes themselves, but even more

importantly to the city-states they

represented. Athletes were revered

for their physical and moral

virtues. Kpatereia , the high degree

of endurance an athlete demonstrated

during the long training period and

his final performance, was

considered a major virtue. An

athlete was expected to suffer in

silence and exhibit patience and

fortitude in all aspects of his

life. The main concern of

competitors was to succeed in a

balanced development of all physical

and moral values. Victory was the

greatest honor a mortal could

achieve. He ‘agonized’ in honor of

the gods and in thanks gave his

victory to the gods, who were

clearly on his side. The favor of

the gods, along with the wide

recognition afforded to the victors’

cities, was the greatest prize. A

victor was crowned with a wreath of

wild olive and afforded special

honors in his hometow.

The spirit and

intention of the Olympic Festival

changed over its long history. The

dedication of a series of

increasingly more magnificent

temples and other structures

designed to facilitate the growing

number of visitors and to honor the

victorious city-states and athletes

were erected. By the Roman period

the sanctuary had acquired

international fame and enjoyed

Imperial benefits. Gradually, the

bond between religion and athletic

activity waned and the games became

secular events, spectacles and even

performances. The Games were then

instituted in honor of the Roman

Emperors. In 393 AD, at the command

of the Christian Emperor of the

Eastern Empire, Theodosius I, the

Olympic Games met their end. Their

reinstitution in 1896 marked a new

beginning with new meaning for the

formerly sacred Olympic Games.

|